How Q-Patrol kept Montrose safe in the ’90s – Chron

The co-founder of an early ’90s Houston gay rights organization has some advice for queer Houstonians and allies who want to fight against harassment and attacks like the one that happened last year in Colorado Springs.

Document everything, says Glenn Holt, one of the co-founders of Q-Patrol, a group that worked with Montrose bars and Houston Police throughout the 1990s to prevent gay-bashing incidents. “If there’s anything going on anywhere, anytime, record video,” says Holt, now 64. “Because everybody has a cell phone, and every cell phone can record video.”

The advice comes in the wake of a deadly shooting in November at an LGBTQ+ nightclub in Colorado Springs, CO, where five people were killed. Numerous other harassment incidents have taken place throughout the United States in recent years, in part fueled by hateful rhetoric by anti-gay groups and politicians.

In Texas alone, at least three drag shows have been disrupted or canceled in the past month due to threats of violence. On December 14, several heavily-armed members of the This Is Texas Freedom Force showed up to protest a drag show at San Antonio’s Aztec Theatre. The FBI and the Southern Poverty Law Center both describe TITFF as a right-wing extremist militia.

A few days later, in Grand Prairie, a group of neo-Nazis known as Aryan Freedom, along with people carrying flags for the American Nationalist Initiative, staged a protest at another drag show. And in Austin, the bar Little Darlin’ canceled a daytime drag queen storytime event after being called “groomers” and “pedo-friendly.”

At both the San Antonio and Grand Prairie shows, which featured performers from RuPaul’s Drag Race, counter-protestors from groups like the Veterans for Equality and armed members of the Elm Fork John Brown Gun Club, a leftist gun-rights group, outnumbered the original protestors. In both cases, police were also on standby. But the events represent a rising risk of harassment or worse for both drag performers and gay bar patrons.

Elder queers are no strangers to such harassment. In the late 1980s and 1990s, Montrose residents and visitors were subject to a variety of harassment and gay-bashing incidents, according to Holt, including homophobic catcalling, being followed, and having raw eggs and trash thrown at them from passing cars. The harassment came to a head in 1991 when Paul Broussard and Phillip Smith, both gay men in their 20s, were murdered in targeted attacks in July and November, respectively.

Gay Houstonians felt that the Houston Police Department was not taking the threats of violence seriously, even after an undercover HPD officer posing as a gay male was assaulted. Frustrated with the police response (or lack thereof), members of Queer Nation Houston gathered together to discuss the reformation of Montrose Patrol, a neighborhood watch group of sorts that existed from 1979 to 1982.

By the ’90s, there were many decentralized neighborhood watch and community groups that had spun out of other organizations like ACT UP, Holt said. A decision was made amongst organizers, including Houston gay rights activist Ray Hill, to consolidate efforts. At the time, some of those groups were also volunteering to help coordinate Houston’s AIDS walks. It was then that Holt and co-founder Connie Sawyer got the idea for the neighborhood’s foot patrols.

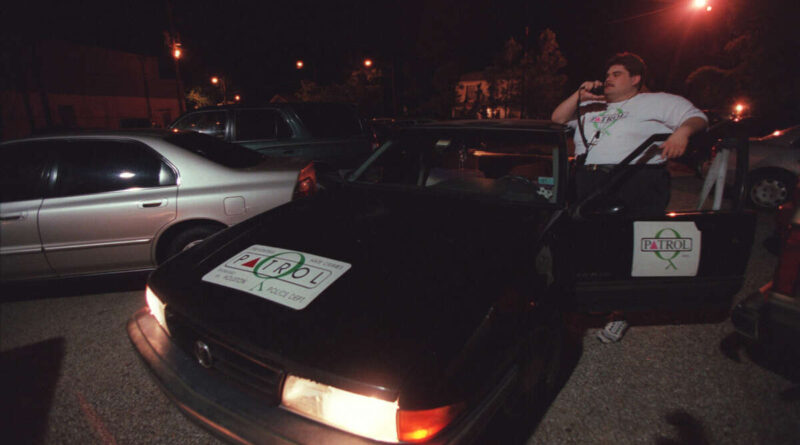

Chris Arasin, chairman and a patrol leader of Q-patrol, patrols a busy Montrose-area parking lot during his mobile patrol near a popular bar district in Montrose 8-26-00. (Camilla McElligott/ Special to Chronicle) HOUCHRON CAPTION (09/05/2000): Chris Arasin, board chairman and patrol leader of Q-Patrol, checks out a busy Montrose-area parking lot during his mobile patrol near a popular bar district. The nonprofit group was formed nine years ago.

Camilla McElligott/SPECIAL TO THE CHRONICLE

“By that time we had some experience with using city-wide two-way radios that we rented, or had been rented for us, for special events like AIDS Walk,” he said. “The whole idea for an organized Q-Patrol occurred to me on the spot that day, when we were handed a box full of radios.”

The group set out to fundraise for their own set of then-state-of-the-art trunking radios, forming a 501c3 to help formalize the process. Soon, groups of four-people foot patrols were walking the streets of Montrose. “We had a lot of people turning out—there was a lot of interest,” Holt said. He goes on to note that, despite some initial distrust on both sides, HPD and Q-Patrol eventually teamed up to offer training.

Each patrol group consisted of a trained Certified Patrol Leader, and usually, someone who was a certified paramedic or first aid certified. Group members wore t-shirts emblazoned with a giant Q, vests, and ID badges. Most importantly, Q-Patrol members had strict rules of non-engagement. No one was allowed to carry weapons. The idea was to monitor the neighborhood, and to contact the police if a crime was taking place. “You’re not going to get personally involved in anything you see, you’re just going to report it, sort of eyes and ears,” Holt said of the rules. “Just being a visible deterrent was enough.”

Holt created a database for volunteers to submit logs of everything they saw—including physical descriptions, incident descriptions, and license plate numbers—which could be cross-referenced later. The squads would stay on watch until after the bars closed at 2 a.m., often walking people back to their cars or homes in the neighborhood.

It wasn’t all serious work. The organization tried to have fun with its efforts, showing up on stage for special performances at the bars and sometimes giving out “fashion citations” which could be cleared with a donation.

Eventually, the need for Q-Patrol subsided. By 2002, the group was struggling to recruit volunteers and donations. “It was harder and harder getting people to come out and actually serve on patrol because nothing was happening,” Holt said. “It just petered out. And that was really what I intended. I never intended for Q-Patrol to continue on past its usefulness. But our success was our demise.”

Much like in Montrose before Q-Patrol existed, the groups that are showing up now to support queer performers and patrons come from various non-affiliated, decentralized backgrounds. Many of the counter-protests are informally organized via social media and text message chains.

Holt thinks that’s for the best. “Q-Patrol was always a visible deterrent to hate crime, but that’s not really necessary anymore the way that society is structured today,” he said. “Anybody anywhere, anytime can record video. The more people that do that, the better.”

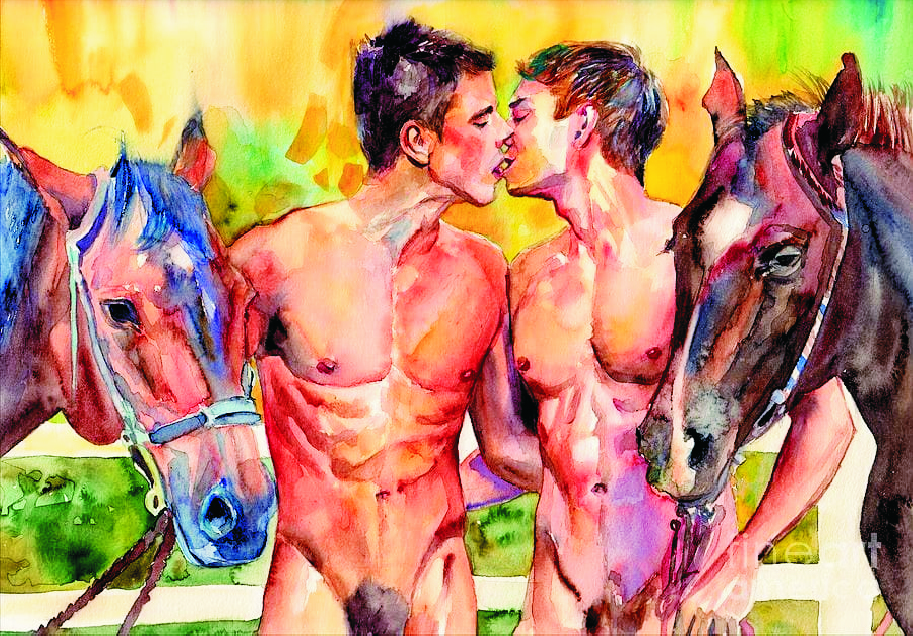

Q-Patrol members Keith Stewart, from left, Christopher Miles and Jan Lee patrol the Westheimer area at Melrose Thursday night, July 1, 1992, in an effort to reduce crime. The citizens’ group was formed in the wake of Paul Broussard’s death at the hands of 10 men who beat him because he was gay. Today, the first anniversary of Broussard’s death, gay community leaders say the Montrose area is a safer place.

Richard Carson/Houston Chronicle

He also said people can take notes of incidents they witness. “Write down as many details of what’s going on as you possibly can think of—descriptions for people involved, what they’re wearing, the locations, the times, that sort of thing. Because any of that kind of stuff would be helpful to police if they decide that something has happened they need to investigate.”

Q-Patrol was an important step for gay visibility and protection in an era without mass surveillance or cell phone technology. While the group was still in operation, Holt and his co-organizers kept immaculate records of their entire program, with the idea that if Q-Patrol needed to be resurrected it would be quick and easy to do so. “Thankfully, society has changed. It really hasn’t been necessary.”

It’s a whole new world, as Holt explains: “I doubt that a bunch of people showing up in Q-Patrol vests, even if the name was known and had a good reputation like it did back then… I don’t know if that would be enough to stop [what’s going on now]. If a bunch of right-wingers decided they wanted to set up shop across the street from a gay bar that was having a drag show, and they wanted to protest—[Q-Patrol] wouldn’t stop that. But what will is peaceful counter-protest, protecting the people who are being threatened.”

More Culture