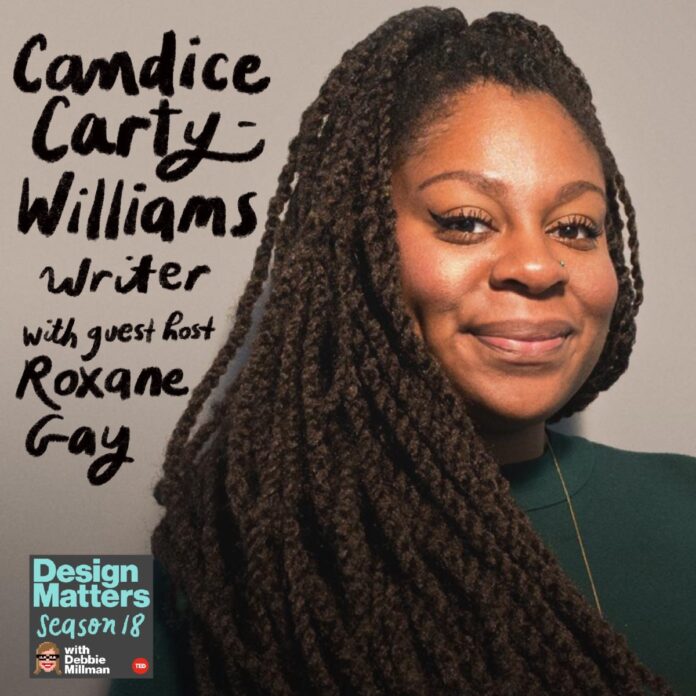

Author of the Sunday Times bestselling Queenie—Candice Carty-Williams joins a very special guest host, Roxane Gay, to talk about her latest novel People Person which follows the Pennington family, a cadre of five half-siblings forced together in the wake of a dramatic event.

Roxane Gay:

A few short years ago, Candace Carty-Williams came out with her debut novel Queenie, about a young Jamaican British woman in London trying to get her life together after a bad breakup. It’s funny and sharp and deeply felt, and one of those books that makes you think this woman is one hell of a storyteller. Well, we’re lucky because now she’s back with her second novel, People Person. And it is the best book I’ve read all year. The novel follows the Pennington family, five siblings really who have the same itinerant father, who has been mostly absent from their lives. When Dimple Pennington runs into something of a crisis with her boyfriend, she turns to the family she hasn’t seen in years. And now as adults, the siblings reconnect and help Dimple solve the biggest problem in her life. And in doing so, they find that the bonds between them are stronger than they could have ever imagined. I am so excited to speak today with Candace about her novels, her work in publishing, and where she goes from here. Candace Carty-Williams. Welcome to Design Matters.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Roxanne Gay, thank you very much for having me.

Roxane Gay:

I am so pleased to see you again.

Candice Carty-Williams:

And me too.

Roxane Gay:

We first met need to in London with the Black Girls Book Club. I’m curious, you’ve said in a number of interviews that you came to writing late and never really thought of yourself as a writer when you were younger. And I’m wondering what was that moment that made writing possible for you where you thought, “Actually, I might be a writer and I can do this?”

Candice Carty-Williams:

Is that day coming yet? I don’t know. I still may be not there, but do you know what it was? It was working in publishing and seeing so many books coming through, but none that I could relate to really. And finding that really hard and honestly writing Queenie was me being like, “Let me give it a go, let me see. I like stories, I like to tell stories, I like to hear stories. So maybe if I try one for myself, it could be something.” Writer, is still something that I’m grappling with. I get imposter syndrome. I suffer from it badly all the time. But I think it was just me being like, “You got something to say.”

Roxane Gay:

How do you go from, “I have something to say,” to a novel because I know that you wrote a lot of the novel at JoJo Moyes’ Country House, which sounds made up when you say it out loud. What was it about that space that opened those flood gates?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I think when I go back to sort of this imposter syndrome thing, I’d won this place on this retreat and I borrowed my friend’s car because I didn’t have a car. And I drove that, I bombed it down the motorway. And when I got there, I just knew that I had to earn my place. And I was like, “You can’t leave without having done something.” And it’s not that Jojo was ever going to come in and be like, “How much have we done?” But I was like, “You owe it to yourself and you owe it to being in the space to produce something from that.”

And so when I got in, I locked myself in there and I wrote maybe 8,000 words I think on the first night because I was like, “You have to do this, You have to this because also you don’t have the space otherwise.” London is a very loud, London is very busy. And I’m one of those people that always, I really try and beat, have gratitude about being in a space that isn’t mine. Or in a space that’s kind of been given to me. And so it was just being very much like, “Earn this now.”

Roxane Gay:

What does your writing process look like when you finally sit down? And I ask that because every time I ask a writer, “How do you do it?” Every writer has a different answer and even sometimes can’t even articulate how I do it. I’m like, “I sit down and most of the time I mess around on the internet, but then once in a while, some words show up.” So what does that look like for you?

Candice Carty-Williams:

It’s in the middle of the night so that I can’t be distracted by the internet or by people. And it’s very intense. And so I will sit and I do a shift of writing for maybe eight hours. And then I will look up and be like, “Oh okay. You’re still here, you’re still fine.” And I won’t have done anything. I might have drunk some water. And then I tend to have a cigarette at the end to punctuate the session. So I know that I’m done, I’m a very weird sort of purist and then I feel quite sick and I feel kind of giddy. And then I have to not do any writing again for another maybe three days, three, four days.

Roxane Gay:

Oh, interesting.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Just to recover. So I’m good at giving myself recovery time because if I try and do it again the next day, my head will explode.

Roxane Gay:

It’s interesting because I do try to write every day, but my best writing, and I will say all of my books were written in very compressed amounts of time. And for many, many hours a day, I wrote my first novel, An Untamed State, writing up to 10 hours a day during a summer. Because I knew this was the only unstructured time I was going to have before a new semester started. And so I just wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. And I was just deeply within the story. And so it’s really wonderful to hear that another writer has a similar process where sometimes you just hit the ground running and I’m a night writer as well. I need everything to be, I need the house to be quiet. I need the animals to be quiet. Yeah. I don’t do well with distraction.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Oh, I do. So I need a lot of noise. I need a lot of music.

Roxane Gay:

Oh, I watch television, I will say.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah. Nice. Yeah no, something in the background. I’m really funny with quiet, so I’m in quiet right now while I talk to you and I’m very, I’m like, “What’s that noise?” What’s that? Who’s over there?” And so as soon as we finish, I brought my speaker with me on this book tour so I can have something all the time. But I love distraction because I think I’ve just got quite a jumpy fast mind and I think that feeds into it.

Roxane Gay:

What kind of music is best for you to write to?

Candice Carty-Williams:

At the moment, so it’s usually been sort of UK rap, lots of grim, but at the moment it’s soundtracks. So Romeo and Juliet soundtrack, that’s a firm favorite. West Side Story, firm favorite. Dream Girls, another great one. And also there’s, oh my gosh, Moulin Rouge, that one. That’s a very good one. So at the moment lots of film soundtracks and I love musicals. I love musicals so much. And so it’s like, “Okay, carry the energy of a musical or the camp all the loud, all the excitement and put it into the work,” if that makes sense.

Roxane Gay:

Yes. I love musicals. I love any situation where people might spontaneously break into song and dance and really make important life decisions through lyrics. Like, “Yes, give me more of that.” And Dream Girls is top 10 show, so good.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Absolutely.

Roxane Gay:

Now, Queenie received such a beautiful reception and I know that one of the things that motivated you to write Queenie was reading all of these books while working in publishing and not being able to connect to many of them. Not seeing anything resembling your life on the page. And now you’ve been able to give that to Black women. And so what has been your favorite moment of having a book like Queenie out in the world? And of course now People Person.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Thank you. It feels like a privilege, first of all. That is an incredible thing to me. And actually I really love being part of something that is a connector of people, that’s super important to me. But I get so many people who just tell me that Queenie made them feel less lonely. And that’s the thing that’s the most important to me because I wrote it because I was feeling so lonely. And when I say that I really had something to say, I just felt so sad always in myself in trying to be this girl, this Black girl who was perfect, who had her shit together. Who was really smart, who was really good at doing her hair, who had the right skin tone, who had the right nails, who had all of this stuff, and who dated properly and behaved properly.

And I was like, “I can’t be alone in always feeling this.” And so whenever I meet somebody who is like, “I’m the kind of girl that Queenie is,” I’m always like, “Okay, good.” Because she’s found her people. And that’s important, that’s me. And also when men read it is always really interesting to me and what their take homes are. But it’s always when women are like, “Yeah, I recognize her.”

Roxane Gay:

Absolutely.

Candice Carty-Williams:

And not just her, but sometimes her mom. I like that connection.

Roxane Gay:

With Queenie, when I read it, I was like, “Oh, I love that. It was a story about a young Black woman who didn’t have it all together. Who was absolutely a mess, who was dealing with anxiety and needing to work on mental health.” And then also just having a sort of precarious living situation, which so many of us have in our twenties and thirties. So I love that you put that book into the world. I’m curious, how do you measure success as a writer? How do you feel like, “Yes, I’ve done good and I’ve made it?” Or do you feel successful?

Candice Carty-Williams:

Do I feel successful? It’s interesting. I don’t know what the measure is. I’m not interested really in money as a metric. I’m not really interested in social media following as a metric. I just like to, if anyone goes on social media, I just sort of post some stuff very irregularly. And my stories are just me doing stupid shit. I don’t have a curated brand. I’m not really interested in being that sort of person.

I think it’s knowing that someone has connected to my work, which takes back to what we’re talking about before. But that’s the thing for me that makes me feel like I’m important and feel like I can talk to someone. Because so much of my life, just as a person is always trying to find a way to connect with people. And I think having two books now where people can come and say to me, “Ah, you’ve captured what I have gone through and I didn’t know who to talk to about, I didn’t even know I needed to talk to about it.” That’s how I measure what success is to me. It’s having found a connection.

Roxane Gay:

Those connections can be so important. I read a piece in The Guardian, and you talked about how Queenie was written about Blackness and response to whiteness, but your second book was a book just about Black people. How have people responded to that difference in focus? And what are you really proud of in People Person and how you grew as a writer between Queenie and People Person?

Candice Carty-Williams:

Thank you. I’ve been waiting for someone to ask that. I’ve had a very interesting response to that, which I recognized quite early on. So I had lots of reviewers and all white ones actually say, it’s not Queenie. And it’s like, “Well yes. Well, of course not, it’s a different work.”

Roxane Gay:

Funny how that works.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Yeah, interesting. And so I think that there is something interesting that I’m finding and when I see plays and when I watch films. There is something about whiteness that is still, whiteness has to be centered even if it’s negatively because it’s at least you still recognize that I’m here. And so the lack of that in People Person I think has really flummoxed people. If there’s not even a lens being held up to me, then what’s the point? And I found that really interesting. So lots of people who were like, “Well, where are the white people?” And I had a journalist, a white journalist, ask me why I had othered the white people in the novel, in People Person. And I was like, “In what way do you mean?”

And she was like, “Well, they’re just the other.” And I was like, “I honestly don’t know what you mean.” I was like, “I’m not being rude, I just don’t know what that is.” And she was like, “Well, the woman in it, she’s described as a white woman.” And I was like, “Well, how would you describe yourself?” And she’s like, “Well, a woman.” And I was like, “Well, that’s the issue.” And so it’s that interesting thing of being like, “Unless I’m writing about whiteness in a way that even is negative, positive, anything.” Unless I’m signpost whiteness is something that is there that is disruptive, then no one really understands what I’m doing. And that’s really interesting.

Roxane Gay:

That is interesting. And it’s always revealing when you press white journalists and readers about their inherent biases about who is the center of a narrative universe. Because it reveals time and time again that what they’re really saying is that white people are the center of the universe. So I’m a woman, but you are a Black woman. You womanhood is qualified by your race. How do you have the, I don’t know what the word is, it’s not courage, but how do you hold that line with journalists and actually ask the questions? Or push back on the question so that they have to confront that sort of bias that they would normally be allowed to skate away with?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I think I try not to do this whole like, “I’m teaching people things.” Because I’m not necessarily interested in that as a sort of function of survival and living. But I definitely think you need to be asked this question and I think I’m going to ask it in a much nicer way than someone else is going to. And so it’s just being patient. And I’ve never been rude to a journalist, so I have had a lot of reason to be. But I’ve never, not because I’m afraid of I’m, I just don’t like being rude to people. I don’t think it’s very nice. But in this, it’s like, “Yeah, I just want you to have a think about what that is and in a space that is safe and in a space that I’m interested.” And I am interested, typically it’s not me being like, “Oh, I’ve caught you out.” It’s me being like, “How did we get here? And how did you get here? And how did you feel that this was appropriate to ask me or talk to me about.”

Roxane Gay:

That’s such a good question of how did you get here? And I’m also interested in the question of where do you go from here with this new information or new perspective? And as journalism goes, it’s rare that we get to follow up with journalists who are interviewing us. But I often think, where are you going to go from here? Is this just going to be an awkward blip on your radar or is this going to be a moment where you have actually learned something.

In People Person, one of my favorite things is that there really weren’t any white people. And it was refreshing and I didn’t realize it until I got to the end and I realized, “Wow, this was just about Black people in a Black community.” And even one of the siblings has a white parent. And even then we barely see her. She only pops up at the end when everyone comes together for something. I would love to know the origin story of People Person, because I loved this book so much, I just loved it. And I rarely say that about a book because there are a lot of okay books. But this was just so warm and so wonderful and the siblings… Tell me about the origin story of People Person.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Thank you so much, that really means everything as you know. So I was in lockdown, paint a picture, I was in lockdown. I was living by myself in a one bedroom flat. And I was incredibly lonely, very, very lonely all the time, obviously as many people were. And I spent a lot of time on the phone to various people as we all did because there was nothing to do. And I spoke to one of my big sisters. So my dad has nine children in total, my mom has two, and there are various step siblings here, there and everywhere. But I spoke to the eldest of my dad’s children with whom I have a good relationship, I don’t have that with the rest of them. And I just said to her, “Oh, what would happen if someone hurt me or someone did something to me?” And she was like, “Well, we would all be there.”

And I was like, “No, you wouldn’t.” And she was like, “No, we would, because even if we don’t all get on, we’re family.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” And then maybe an hour later I was like, “That’s going to be a novel. That’s what I have to do.” And I’d written another version of People Person before the one that you see in front of you. And I wasn’t vibing with it, I didn’t like it at all. And I’d done so much work on it. And I was halfway through the edit of that in lockdown, and I was like, “I just don’t care about this.” And so as soon as I started writing this new version of People Person, I could feel so connected to it. And I was like, “Okay, yeah. This is a sign. You just have to keep going with this one.”

And I off my editor, I pissed off my other editor, I pissed off my agent, I pissed off everyone. But I was like, “But you want me to talk about what I care about and what is real?” And it also occurred to me that I hadn’t read anything about Half siblings. So many people have them, and it’s such an interesting and delicate and often unsuccessful relationship, I think. And I would love for people to be able to talk about those things because I grew up with, as I’ve just said, so many half siblings. And I talk to a fraction of them. And that’s really, really hard. And it’s kind of like, “Okay, well…” A lot of my work in some ways is always, I guess, Queenie in some way was fantasizing about who I would be if I didn’t have to be sensible. And didn’t have to be in control all the time.

And this was fantasizing about what would happen if I did have a relationship with my half siblings and I wasn’t even necessarily Dimple. I think that I put bits of myself into all of those characters. I think I could only write them well because I believed in all of them and I believe in all the different bits of them that make up me. But it was definitely me exploring that. And then of course when it comes to dads, the relationship I have with my dad is effectively non-existent. Someone asked me at an event yesterday like, “Oh, has he said well done? Has he read the book?” And I was like, “Are you joking?” Like, “Of course, what?” They said like, “That felt like such a mad question.” And so thinking about dads and thinking about what it means to people when there is someone in your life who you are always taught by TV, by other books. By your friends, by other family members that you see, you are taught that this person is meant to love you and meant to care about you and meant to check in and meant to protect you.

What does it do when that doesn’t happen? What does it do to you when that doesn’t exist? And what does that do to five people who are very, very different in their ways? And how affecting is it when they are just going through life, not necessarily incomplete, but definitely with questions? And definitely understanding at some level that there was rejection there and how do they do that? And so my whole thing was like, “These five cannot reject each other. I can’t let them reject each other though way they’ve been rejected.”

Roxane Gay:

One of the things that I thought was most compelling about the book, most honest, and as a writer, just truly audacious, is that we have this, I think desire, at least I do, to give the reader everything they could possibly want. And then I pulled that back and give them about 85% if I could put a number on it of what they actually want. And what they think they need from the book. And toward the end, as the kids have dealt with the primary obstacle, but there’s still like, “Okay, now what do we do? And how do we engage with our father? How do we get him back in our lives?” And I don’t want to spoil the book for people, but you made a really interesting choice where you didn’t make the easy choice. How do you make difficult decisions in your writing and how do you make those difficult choices where you know that you may not satisfy every reader, but you satisfy the story instead?

Candice Carty-Williams:

So actually, it’s funny, I did the same thing in Queenie in a different way. I remember so many people have come up to me to be like, “Cassandra should have got what for? I can’t believe you let Cassandra get off.” And it’s like, “Yeah, but it’s good for the story.” I think it took me a long time to sit in this in myself. And this was when Queenie was coming out. I’m just thinking about how I like to do things in the world. And I thought, you can’t do this for everyone else. And I, of course, there were 10 versions of People Person that could have ended the way that I think would’ve served everyone. But that didn’t serve me as the writer and it didn’t serve my story. And it’s my job, I think, to be like, “What is the story that you want to tell? And you can only tell it convincingly if you tell it in the way that you need to.”

And so, yes, the ending of that, and actually lots of choices that I made in that were difficult. But they were followed because I was like, “But that’s the thing that’s authentic to me and that’s what the story is telling me to do.” And so I will listen to the story before I listen to anyone else. But when the book comes out, I love hearing from people. I love hearing their quivals. I love hearing their arguments. Queenie got a lot of shit as a person. And I had to keep saying to people, “She’s not real. This is a work of fiction.” And I wrote her this way because I knew it would, I wanted, it’s a story.

But I think she was so frustrating to say to people, that people forgot that she wasn’t a real person. And it elicited such a passionate response. And sometimes quite an angry response. And sometimes people are really being pissed off with me. It’s a bit intense. I think there is a space between writing the story and then the story coming out where I’m like, “You need to do what you need to do.” And then you just deal with everything afterwards. And I really like that. And I really like that it doesn’t make me uncomfortable. I like making people feel things that they wouldn’t necessarily feel if I’d just given them the story that they’d expect.

Roxane Gay:

So there are five siblings, Nikisha, Danny, Lizzie, Prince, and Dimple. And I noticed that all of them were distinct, which is challenging to do when you have an ensemble and you want people to understand that these people are connected, but they are also individuals. And so how do you build characters and how did you ensure that they would be distinct characters?

Candice Carty-Williams:

So I feel like this is a hack, but I just start with Zodiac signs. It’s the easiest thing ever for me.

Roxane Gay:

Oh yes.

Candice Carty-Williams:

So I’m just like, “Who is this person?” So Nikisha is an Aries, clearly. Danny’s obviously a Gemini. Dimple is a cancer. Lizzie is a Leo, and Princes are Sagittarius. And then it was like, “Put those five signs in a room, what’s going to happen?” And it was just the easiest thing. So I had so much fun being like, “Okay, so the most difficult relationship is going to be, I mean, Dimple in kind of everyone, because Cancer’s…” I’m a Cancer myself. And I’m so feeling that so many of my relationships were when I was younger, difficult because I didn’t understand why people didn’t feel exactly like I did. Why they didn’t respond exactly like I did. Why they weren’t quick to emotion like I was, I couldn’t get it.

And then as I got older, I was like, “Okay, star signs, think about this stuff.” And I started to get really into it. My mom was really into it, and I would always be like, “Okay, whatever.” But then I got older and I was like, “Oh no, this actually helps me as a framework for people.” And so I knew that having Dimple as a Cancer, her being that central point, those relationships that she was going to have, especially with Lizzie as a Leo, that is going to be very difficult. But also Nikisha, who would be always telling her what to do. And it’s like, “Why are you telling what to do and not thinking about my feelings? My feelings are so…” And then Prince, who is Sagittarius, it’s like, “Nothing sticks.” And her being like, “Everything sticks on me. Why does nothing thing stick on you?” And then Danny, who’s just this sort of wide thinking, Gemini, who’s really optimistic because he’s not bogged down by anything and he’s not bogged down by his past in particular.

And just thinking about Dimple and these people, but also the rest of them. And honestly, star signs is just my favorite thing because I just know what I’m dealing with. And so very simple. And just even down today, they would talk to each other and the way they would talk amongst themselves. And also the journey of them. So if I take two characters, Lizzie is a Leo, as I said, she’s very upfront. She’s going to say things, she’s going to call things, how she sees them.

And what we learn about her through her life is like, “Okay yeah. This is the person that she is.” But it’s not a surprise. It’s not a tell because we know how she’s going to operate. But Danny is a lot slower because he’s not urgent. He’s just thinking about things and taking the day as it comes. And so as his story is revealed, and it takes a lot of time, it takes time because Danny takes time. And so it’s just thinking about how they would be and how they are telling us who they are, just from that standpoint. And so I just had a very clear vision of them just with, I will always use Zodiac as my starting point because I don’t know, it just helps. It just feels like I have a great trick, like I’ve tricked everyone.

Roxane Gay:

I’ve never heard that before. And it makes sense. I mean that really, it really makes sense. I’m a Libra, so of course I would think it makes sense.

Candice Carty-Williams:

No, I know. Aren’t you a triple Libra?

Roxane Gay:

I am like a quintuple Libra. I have all but one of my suns are moons. A couple years ago for my birthday or anniversary, my wife got me a private reading by Chani Nicholas.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Oh, [inaudible 00:25:18] a dream, the dream.

Roxane Gay:

Oh. It was so good. Everything was in Libra. And I was like, “Yes, that tracks.” Seeing how these characters, yes, come together. And when you describe them through the Zodiac, I was like, “Yes, I know these people. I know them.” You mentioned your mother was very into the Zodiac.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Yes.

Roxane Gay:

What kind of relationship did you have with your mother growing up and now?

Candice Carty-Williams:

Gosh, my mom, I really love her. She’s a Gemini, it’s difficult. It’s difficult because she’s like a fucking fairy. I’m very far from a fairy. I’m very realistic. I’m not pessimistic, I don’t think, I’m very realistic. And she is optimistic to the point of delusion sometimes. But we get on, we had a difficult childhood, I would say. There was a stepdad involved and she just wasn’t able to be present in a way that I would’ve needed from her. But it was okay because my Nan swooped in and was like, “Right, fine. I look after you.” And other family member swooped in and they were like, “Right, well, she needs help.” And actually a lot of the stuff that we’ve worked through recently, a lot of therapy, a lot of my stuff has been around, I guess, acceptance and forgiveness of that. But I’ve always known that throughout everything, she’s a very kind person.

But I think that her optimism is a thing that gets her carried away and she flips off and she’s like, “Oh.” Like we will go to, I remember there were a few years of my life where I was suffering from terrible, terrible anxiety. And she’d dragged me somewhere, she’d be like, “No, you should come. I’ll stay with you the whole time. We’re going to have a nice time. I’ll look after you.” We’d get in and she would see her friend the second she stepped through the door and run away. And I wouldn’t see her for three hours. And so I was always like, “Oh, okay. That’s how it is.” But as time has gone on, I don’t want to say she’s like a friend because I still call her when things are upsetting. That’s the person that I want to speak to. And so it’s a relationship that I’m really happy that I work towards. I don’t want to say mending, but I work towards understanding, if that makes sense?

Roxane Gay:

It does.

Candice Carty-Williams:

And so she’s kind. That is so underappreciated sometimes.

Roxane Gay:

It does seem that way sometimes. And I value kindness probably above all other things because it can do so much and it can go such a long way. You can have other deficiencies, but if you’re unkind, I just don’t see a way forward.

Candice Carty-Williams:

I agree.

Roxane Gay:

But if you are kind, then we could probably work almost anything out. You’ve spoken very openly and eloquently about childhood trauma and dealing with anxiety and also getting healthcare through therapy. What prompts you to be open about the things that we tend to try and keep to ourselves instinctively?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I suffered so much when I was young with being this sort of strong Black woman. And I just wanted someone to be like, “I’m not, that’s all I wanted. I just wanted one person to be like, I’m not that strong.” And I never had that. And I was seeking it for years and years. Not in my family, not around my friends, not on social media. And so I made a decision when I had any sort of public profile to be someone who is like, “I’m not a strong Black woman at all.” And that’s fine because I’m sure there is someone out there who’s going to be like, “Well, great, neither am I.” And also it’s like, this is a very strange, you’ve seen 8 Mile, I imagine.

Roxane Gay:

Yes, I have.

Candice Carty-Williams:

And I think you just like Eminem does at the end, Rabbit, you just got to say the stuff people might say about you up front because there’s nothing I’m ashamed of. In my bio it says that I’m the product of an affair. That’s true. And had this idea of a journalist being like, “Oh, so your parents, were they together?” And me having to be like, “Oh.” And maybe someone finding out that. And I was like, “No, I’m never going to have anything that anyone can use against me.”

And so I think it’s two things, it’s like, I don’t know, I think also I’m a person in the world. I’m not perfect, I have many flaws. I’m trying to work them out. As we say, I’m trying to be kind as I do it, but there’s nothing about myself that I’m ashamed of or embarrassed of. And I don’t think anyone should be, because I honestly think so many of us are just trying to get through the day. And so I think this idea that I’m strong or that I’m impermeable or that I’m the best or that I can do everything that other people can’t do, it’s just not real. And so I think, just say it because we’re all just figuring it out. And that might sound naive or quite silly, but we are, everyone is just trying every day to deal with something.

Roxane Gay:

It doesn’t sound naive. To my mind it sounds realistic because it’s the truth. And sometimes the truth is just plain and simple. You were raised in South London and you said that you’re going to always live there. What makes South London home to you and what holds you to that place?

Candice Carty-Williams:

That is a really beautiful question for my heart. South London feels very safe to me, I think because I’ve been there a lot. But also because I’m quite a sad person, which is fine. And in a way that I’m cool with that. It is cool. I can have a laugh and I’m funny, but naturally the emotion is sad. And I’ve spent a lot of years walking around South London, being sad, listening to music, walking around parks all times of night, all times of day. And I’ve always felt very held still, always by this space that’s always looked after me.

It feels very consistent. And it is the most consistent thing in my life. I’ve moved around a lot. I worked out that I lived in, maybe I’ve lived in 25 houses when I was growing up and they were all in South London. And I always felt okay because I knew that I was going to be in this place that I understood. And so for me it’s that and it’s the nostalgia of always walking around this place and always feeling okay. And always knowing I was going to be safe and I always was. And I hope that I continue to be, but I’ve always been safe and held by that particular area, which is very interesting. I don’t know if many people have that, but I know it and I long for it.

Roxane Gay:

Safety, I think like kindness can be underrated. I think it can be overrated in certain contexts, but I also think especially for Black women, it can be incredibly underrated. And when we do find places and spaces that are safe, they are invaluable because there are so few of them, quite frankly. Before you were a writer, you worked in publishing quite a lot. And in fact when I met you, I think you were still at Fourth Estate. I know that being Black and publishing in the United States is challenging because there are very few people in publishing, editorially as agents, as marketing executives, which is where you were. How did you navigate publishing as a Black Britain?

Candice Carty-Williams:

How did I? How do I answer this question diplomatically? In my first job I had, and legally, in my first job, I had a really fun time. Fourth Estate was really amazing to me. I was able to start the short story prize with the Guardian for Underrepresented Writers. That was incredible. And that was me being like, “I have an idea, I have a plan.” And them being like, “Okay, do it. Enjoy yourself. If you need us, we’re here. You can chat to us.” That was incredible. And so I had a really good time there, but I think, because I was 25 and I was sort of just running around drunk all the time. Just doing stuff I shouldn’t have been doing. That was okay. And publishing understood me as a young person. And so most of the seniors would say to me and my friend who I worked with that time, my best friend, they would be like, “Oh hey kids.” And that was cool.

And then I went into my next job and it was not as, it wasn’t good at all. I felt the weight of being the only Black woman. There were many, many incidents that I found very, very tough. And I would’ve loved to have stayed on and carried on working publishing, because I know that when you have someone Black or someone of color working somewhere, it makes a massive difference to what is published, even if it’s one person. Because it just takes one person to stand up and be like, “I can see how this book would sell. I can see why it’s important.” But I had to go. I had to go. And for many reasons that basically they paid me off in it. But one day I reckon, I took a break and give them their money back.

But I had to go. I had to leave because I was like, “It’s killing me. It’s killing me. It is killing me being here. The weight of that is hard.” And I’m a very resilient person. I always have been. I can do a lot. I can feel a lot and I can cope with it. But that place, I was like, “I don’t think I’m going to make it out alive.” And so I had to go. And I think writing a novel, I was asked by Human Resources, “Did you get permission to do that from your boss?” And I was like, “Ah, okay. It begins.” So it was a time.

Roxane Gay:

I have to say, every time I talk to a Black person in publishing, I hear a story and I think I’m never going to hear anything more fucked up than this. And then I talk to someone else and I hear something worse and I think, “Okay, this is it. This is the apex. I’m not going to hear anything worse.” When you’re asked, “Did you ask for permission to write,” that hearkens back to so many white supremacist activities like enslavement. Are you kidding me?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I mean, I laughed. I laughed because I thought it was a joke. And I was met with just a very straight face. And I was like, “Oh, that’s not a joke. You are serious.” And I was like, “No, of course not.” And at that point I was so kind of like, “Oh, should I have?” But I was even then I was like, “This isn’t right. That’s not right.”

Roxane Gay:

No, it’s not. It’s curious to see the ways in which employers tend to think that because we work for them for eight hours a day or so, that they have ownership over all 24 of our daily hours. When such is not the case.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Absolutely not.

Roxane Gay:

Do you think publishing has improved in recent years as we’ve had more open conversations about diversity, inclusion, representation?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I think it has improved. I am hopeful that the change is here to stay. So every hopeful part of me genuinely does think that is the case. Because I look around when I go to book events and I see that the workforce is way different to how it was when I started in publishing. And when I started publishing, which was maybe, let’s say 10 years ago now, things were in vastly different and for the worst. And so when I look around and also I see what’s being published, and I see that the literary landscape for us is so much broader and it’s so varied. And that’s important because I think that there was a time when it was all the slavery books were the thing, and then it was like, “Okay, all the books about being African and in Africa, nebulous Africa with a thing.” And so now it’s like, “Okay, we do see different stories and different backgrounds and different perspectives.” So I remember working on a book, Behold the Dreamers, which was by a Cameroonian author…

Roxane Gay:

Oh, Imbolo.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Imbolo.

Roxane Gay:

Yeah, great book.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Beautiful book. And I remember just the way they tried to market was just, I think for some reason it was like send it to these Nigerian influencers. And I was like, “You don’t understand.” So it’s like you just have to have people who are in there, people who can pick up on the nuance, which isn’t actually nuanced to us, but you know what I mean. And make sure those things are correct in the way they got into the world. And so to answer your question, I think it’s better. And I’m hoping that it’s sustainable.

Roxane Gay:

I am too. I think that’s the real measure because I’m often asked the question I just asked you. And I don’t think we have seen improvements that are commensurate with the amount of discussion that there has been around the issue. And the amount of promises publishers have made about addressing the issue. And every time there is a step forward, there’s a step back where, for example, senior editors at a major Black imprint are suddenly fired from that imprint. Which is something that recently happened at Amistad, at Harper Collins in the US. And so I’m always curious as to what it’s going to take for sustainable change to happen, which is the real measure. How long can we sustain this where we have more inclusive editorial culture and every other culture within publishing so that people don’t think Africa is a country. I can’t believe sending a Cameroonian author’s book to some Nigerian influencers. God bless them.

Candice Carty-Williams:

But that was the whole plan, that was and I was like, “Oh, okay.” I was like, “Let’s get a focus group together so I can prove why this is so wrong.” And so I think you need those people who are going to just be there and be like, “That doesn’t make any sense. But again, let me show you in a gentle way why it doesn’t make sense.” It’s exhausting. I don’t do and I don’t miss it. I would go back into it. People ask all the time, “Would I?” I would, I would go back in. I would, I would go back in. I loved marketing so much and I would go back into that.

Roxane Gay:

You are a writer now full time. And I’m curious, are you working on your next novel?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I’m not at the moment because I’m show running one of two TV shows that I’m working on. I’m working on a TV show called Champion, which is a musical of course. And I am working on the adaptation of Queenie. And so there is no time for a novel. The adaptation Queenie is a fucking headache because adaptations are hell. Because it’s just like, “Why buy the book if you want to just do your own thing with it?” That’s interesting, just get someone to write something different. You know?

Roxane Gay:

I do know.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Yeah, I’m sure. And I’m really candid about that. And I don’t really care who hears it because it’s like, “Why buy it? I don’t understand why you would do this.” And so I think I’m going to have to earmark my time to get back into novel writing. I think end of next year. TV is a really, really… I feel like I’m trapped in a web and it’s going to take a long time to extract myself from it because there are so many moving parts. And when you’re show running, you have to be there all the time. You have to be active and engaged and you have to talk to people all the time. And I just think when I started writing, I never thought I’d end up managing anyone. Do you know what I mean? You just sit.

Roxane Gay:

I do. I do.

Candice Carty-Williams:

You just sit and then I’m not I’ve got to-

Roxane Gay:

I’m show running a show and I’m grateful for the work.

Candice Carty-Williams:

As am I.

Roxane Gay:

It’s not what the dream was.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Do you sleep?

Roxane Gay:

Not enough, not enough. Not enough and my shows have not yet moved into production, which I know is going to amp things up immeasurably.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Oh yes.

Roxane Gay:

I really am grateful for the work, but when I dreamt of being a writer, all I dreamt of was books. And that really would have been enough. This is not something I ever anticipated. And of course I do enjoy it, but it’s a different beast. Book people, I know what to expect from book people for better and worse. And TV people are just buck wild. They’re just buck wild. They don’t care. They’re going to do what they’re going to do.

Candice Carty-Williams:

Nope. Absolutely.

Roxane Gay:

He who has the most money wins and they have the most money. So it’s very interesting to see what happens with adaptations. Are you also writing the adaptation of Queenie?

Candice Carty-Williams:

I’m writing some of it, but not all of it. Because I think my thing is, Queenie came into the world with me, and I put her out there. I was able to be like, “This is what this book is about. This is why I care about it.” And I think that I’ve done that work now. And I think that when it’s a TV show, it’s a different life. It’s a different thing. And I would actually be okay to be like, “Someone else can do that.”

But there’s a really amazing bunch of writers working on it, and it’s been so fun and collaborative and that’s been one of the best parts of it. Sitting in a room with other Black people, just sharing our experiences and really, really… And men as well, Black male writers who were like, “Yeah, I know this and I understand this and that. What’s this?” And who ask questions as well, crucially. But when it comes to actually writing the thing, I’d like to back up, I’d like to step away from it because I’ve done it. It’s eight years since I started writing her, I don’t need to do it again.

Roxane Gay:

I have one final question, which is a question I like to ask every writer that I have the pleasure of speaking with. What do you like most about your writing?

Candice Carty-Williams:

That’s a lovely question. Do you know what I like most about my writing? I like in my writing the way that I speak. I do what I want, and then you just catch it and take what you want from it. That’s what I like. I don’t try to write or speak like anyone else.

Roxane Gay:

I love that. Thank you so much. Candace Carty-Williams, latest book, hot off the press is People Person. This is the first time I’ve hosted Design Matters, but this is the 18th year of the podcast. Both Debbie and I would like to thank you so much for listening, this week and every week. And remember, as Debbie tells us, we can talk about making a difference. We can make a difference or we can do both. I’m Roxanne Gay and Debbie is looking forward to talking to you again soon.